I started running track & field at Grandville middle school in 7th grade. Like my son Steven, MITCA (Michigan Track Coaches Association) 2012 boy’s high school track athlete of the year, we were both good jumpers and pole-vaulters, but not sprinters until the eleventh hour of our high school careers.

In the summer of 1973 I had just completed the 8th grade. I spent a lot of time in the Grandville Public Library, not because I loved books but because the library and one other public building in town were the only two places that had air conditioning. It was a hot summer day when I stumbled upon this book about Bob Mathias, Olympic Gold Medalist and the “Grueling” Decathlon for the very first time.

I flipped through the pages of the book primarily focused on the old photographs. Page after page, I saw Mathias wrapped in blankets, his mother, father and brother in the photos tending to him as if he had the flu or he had just emerged from a World War II army fox hole. The majority of the decathlon photos of Mathias were taken in the middle of the night with no spectators or stadium seen in the background…it was as if he was competing on the moon. Mathias, and the other competitors all had that same gaunt, “ Where the hell am I,” stare…the same expression we’ve all experie

I flipped through the pages of the book primarily focused on the old photographs. Page after page, I saw Mathias wrapped in blankets, his mother, father and brother in the photos tending to him as if he had the flu or he had just emerged from a World War II army fox hole. The majority of the decathlon photos of Mathias were taken in the middle of the night with no spectators or stadium seen in the background…it was as if he was competing on the moon. Mathias, and the other competitors all had that same gaunt, “ Where the hell am I,” stare…the same expression we’ve all experie nced when our mom woke us up for school in the middle of a dream, only to realize there was no snow day off after all.

nced when our mom woke us up for school in the middle of a dream, only to realize there was no snow day off after all.

I revisited the Mathias book several times over the next month every chance I could. Eventually I worked my way from the bleak images and started to read what this event entailed. It’s good I was ignorant about the changes in the high jump and pole vault marks that Mathias posted in the London Olympic Games. It caught my eye that I was high jumping and pole vaulting very near to what he did in London and I was only 13. What I did not realize was he landed in dirt in both events while I landed in soft cushy mats. I had no clue there was no such thing back then as fiberglass vault poles or the Fosbury flop either. Well, ignorance was bliss, so I went about falsely comparing my marks to Mathias’ 1948 London Olympic Gold medal performance.

|

|

As I continued to compare myself to Mathias in that book over the next couple years, I figured the only thing I was missing was some speed. Again, just like my son Steven, though we were fast in elementary school, we each looked like 6th grade boys entering 9th grade. By the summer of my junior year though, growth and the speed unexpectedly arrived. In both my junior and senior years in high school, I had posted one of the top three high school decathlon scores in the nation. My freshman year in college I won the National Junior Decathlon Championship and finished that season running for the USA team and defeating the Soviet Union junior team in Donetsk, Russia. Honestly, I doubt I would have ever taken up the event but for the fact that the cheap Dutch store owners in Grandville would not invest in air conditioning. Thanks to them I ended up in the library learning who Bob Mathias and the decathlon were and it ended up paying for college and gave me a chance to see the world.

The decathlon was only added to the NCAA Division I meet in 1974 and the spring of my freshman year in college was 1978. So a combination of the qualifying standard for the national championships being lower back then (7,200 hand timed) because it was still a relatively new event and some dumb luck, I am still one of a handful NCAA Division I decathletes ever to qualify in four consecutive years for the national championships. Having participated in four consecutive NCAA meets, twelve total national championships and USA teams during that era, I can tell you, the decathlons were a much longer, grueling affair back then.

I didn’t know it at the time and the sport will hardly note it, but I had the unique fortune to compete in one of the only three day decathlons held at the NCAA Division I Championships in 1978. We finished running the 1500 meters at 1:30 am Pacific time, (that was 4:30 am, Michigan time) on day three.

I didn’t know it at the time and the sport will hardly note it, but I had the unique fortune to compete in one of the only three day decathlons held at the NCAA Division I Championships in 1978. We finished running the 1500 meters at 1:30 am Pacific time, (that was 4:30 am, Michigan time) on day three.

In the early morning hours of June 1978, in Eugene, Oregon, Hayward Field, I laid down on my back and put my feet up on the green wooden, planks of the iconic grand stand along the backstretch of the track. I would always prop my feet up before the 1500 meter race and when my feet would start to tingle I knew I was good to run again. Since it was 4:00 am Michigan time, I fell stone cold asleep only 15 minutes before running the final event of the decathlon.

I was awakened during a dream of my mom calling me to get up for school… the snow day had been cancelled. I awoke to an even more “grueling” reality than a cancelled snow day. It was 4 am, my last sit down meal was breakfast 22 hours earlier and I was being told by my coaches I had to run the 1500 meters at 4 am. You remember the face I spoke of earlier…the dumb-founded blank stare? It was “grueling” to think I was dreaming a few moments ago and in a few minutes I was supposed to be running a 4:20 1500.

At that time, Hayward field did not have any lights. So for the javelin, they pulled cars on to the track, about 8 on each side of the infield illuminating the landing area and the judges. The sand colored track and Hayward Field grand stands that were drenched in colorful sunlight hours earlier were now covered in darkness, as if a wrecking service had hauled them away on a truck. POOF… they were gone. The line of cars illuminating the final flight of the decathlon javelin made the venue even more surreal, like a scene from a close encounters movie, surrounding us with backlit alien-like silhouettes of the athletes and officials. The lack of food, sleep, and drained mental stamina were taking their toll. I was in a daze.

It was then I was shaken from my stupor by a sudden flash of déjà vu. Was I dreaming? No… I had seen this place before. And without holding up a mirror I knew the cause for concern on my coach’s faces was the look on my face. I was now wearing that grueling decathlon death mask. It was that same hollow, gaunt face I had seen years ago in that book about Bob Mathias and the grueling decathlon. The stage was the same as well. The stands had faded to black; the spectators were all in bed. The morning dew made you long for a wool blanket and cup of coffee and your parents and brother close by, just in case you did happen to keel over from lack of food, sleep and exhaustion. It was 4 am Michigan time and in the total darkness of Hayward Field, it looked as though the last event was going to be competed on the surface of the moon…just as it did in the Mathias photos, years ago in my home-town library.

I did 37 decathlons during my career. All but two, the Olympic trials in 1984 and the USOC National Sports Festival in Baton Rouge, LA in 1985 used one set of pits in the long jump, high jump and pole vault. Before 1984 it was unheard of to ever use a two pit system in the decathlon. Once when it was tried at Drake Relays in 1981, we protested it as an unfair advantage since both jumping areas or even pits and cross bars weren’t comparable. We actually won the protest.

|

Before the two pit system was being used during a decathlon, it was standard the pole vault competition would last five, sometimes as long as nine hours from start to finish of the vault. The high jump would last three to six hours. The long jump would take about two hours or more. What did the advent of the two pit system do? First, it changed the decathlon from 23-28 hours over two days, to a two day event these days I have witnessed taking as little as 8 hours.

The practice of using two pits in the decathlon in the long jump, high jump and pole vault has changed the decathlon, favoring the superior sprinter. A two day decathlon with two pits used for the jumping events can be completed in 8-12 hours. Before 1985 a two pit system was a rare occurrence. By contrast, when a one pit system was used, OFTEN a superior sprinter would fade during the pole vault, javelin and then the 1500, just by virtue of less over distance training and his abundance of white twitch muscle fiber. Simply, they often had trouble enduring a 23-30 hour decathlon that used only one set of pits for the three jumping events. They were usually either injured, or faded terribly in in the last quarter of the competition. Decathletes that could run a 4:12-20 1500 loved this. Reporters and die hard spectators stuck around to witness this. The favored athlete did not always necessarily win. Few note that both Olympic Gold Medalists Bill Toomey and Rafer Johnson each only came one missed jump in the vault (Toomey 1968) and 67 points (Johnson in the 1500 in 1960) from losing their cherished Gold medals. Had Toomey missed his final vault attempt, he once said, “ I came one vault from becoming an Olympic Gold medalist or the biggest beach bum in California” The point is, the longer, one-pit (for the three jumps) decathlons were 25 plus hour affairs, and favored athletes simply melting down during competitions happened, OFTEN. The decathlon was a game of survival, and not just a sprint fest. It has been years since I have heard a coach say of a decathlon prospect, “He is a great athlete, but I don’t think he has the mind to be a decathlete.” What they meant by this is an athlete’s ability to perform when the body is exhausted, hungry and the fatigue talks to you like a demon on your shoulder telling you to quit and save yourself. The great decathletes had the stamina to flick the devil off and tell it go to hell.

The decathlon was not supposed to measure the fastest sprinter, that is why we have the 100 meters. The decathlon is supposed to measure the best all-around athlete; this should still include measuring stamina. Not that a 1500 meter race is long enough to measure endurance, but I imagine the 1500 was chosen for the decathlon over the 3000 meters as the endurance event because the original decathlon had athletes out there 25 plus hours over two days. With only a 9-16 hour decathlon, maybe it’s time to introduce the 3000 meters as the final event and get back to a decathlon that measures staying power and stamina, not just raw speed and brute strength.

Of the 37 decathlons I did, the shortest one was 20 hours. I saw a decathlon at the Sea Ray Invitational in 2009 that was over in four hours on day one and probably five on day two. Sure, it’s a decathlon, it has ten events but it has almost become an imitation of the event depicted in the photographs in this article. I am not proposing in any way we lengthen a decathlon or seriously add a 3000 meter race. But the combination of better officiating and the two pits used in the jumping events has shortened the length of the game. It would be like ending a pro basketball or football game at the first half. It affects all records since it is much easier to play a faster, more accurate game that only lasts 50% as long as the games that were played for two halves and double the time.

|

Look at the pictures of all of the decathlons I have throughout this article. Note the one thing they all have in common. They are all finished in the pitch dark of night. They were all 20-30 hour contests. And just like my first NCAA Championship I was in my freshman year, the term grueling was not coined because the last events of each day, of a decathlon are the 400 and 1500 meters. The one pit decathlons were grueling because of the amount of time waiting, staying loose enough to relax when you could and ready enough to perform when you should for over 25 hours. Your fitness had to go beyond just being a sprinter. You had to have enough endurance to make it through the 25 hours of competition. For many great all-out sprinters, it was not enough to just be fast and strong, you also needed to have stamina just to be out there for 25 hours. There were no Cliff Bars or protein drinks; you experimented with what to eat to sustain yourself during the 25 hour ordeal. I found at about my 20th decathlon that if I ate raw potatoes and baby formula (Similac) I threw up and crapped my pants less during a decathlon. I don’t think a lot of pant crapping goes on in a 12 hour decathlon these days.

With the two pit system and a two day, 10 hour decathlon, an outstanding sprinter who can long jump 27 feet is almost certain to win the decathlon. It just was not so when the decathlons were 20-25 hour, one pit affairs. I once was trailing NFL Pro Bowl punter Rohn Stark (Indianapolis Colts) by 150 points in the decathlon going into the 1500 meters. I won the meet by 100 points by the simple fact that the “grueling” aspect of the decathlon, stamina, got to him because he was a big person and sprinter and he had trouble being out there 25 hours. I have no doubt had the meet been on a two pit system and lasted only 10 hours; he would have easily won that meet.

The decathletes today by no means have it easy even with only a 12 hour decathlon over two days. But they do have an almost “plush” experience compared to the grueling decathlons that existed before 1985. So I chose to write this article not to seriously suggest changing to longer decathlons or promote we run a 3,000 meters. But I wrote this to address comments I have read on blogs and even overheard in the stands at the NCAA championships a few years back, people who were saying Mathias, Rafer Johnson, etc. really were not very good. I hope you realize the decathlon of today is not the same event it was the first 85 years of the 20th Century.

Decathlons are considerably shorter with the two pit system. With only the best intentions, at around 1984, meet officials started using two pits and shortening the length of the decathlons (just as they should and just as I would have if I were running meets). And somewhat by accident, the two pit system has changed the decathlon by shortening the length of it. Today’s decathlon has abbreviated playing minutes, is much shorter and has turned the decathlon into a test measuring speed and strength…some endurance., but no longer grueling stamina to have to compete for 27 hours.

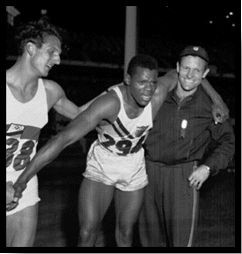

I am including a picture of Bob Mathias here on the cover of Time Magazine. There was a time when the decathlon had such a legendary lore of survival about it, that being the Olympic Decathlon Champion was almost like performing a feat equal to Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic or Armstrong landing on the moon. Why was it such big news? Because the reporters that stayed the night to witness and write about the late night battles of survival of Mathias, Milt Campbell, Bill Toomey, Rafer Johnson and C.K. Yang saw how this event, after 25 hours of competition, humbled even the best athletes.

I am including a picture of Bob Mathias here on the cover of Time Magazine. There was a time when the decathlon had such a legendary lore of survival about it, that being the Olympic Decathlon Champion was almost like performing a feat equal to Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic or Armstrong landing on the moon. Why was it such big news? Because the reporters that stayed the night to witness and write about the late night battles of survival of Mathias, Milt Campbell, Bill Toomey, Rafer Johnson and C.K. Yang saw how this event, after 25 hours of competition, humbled even the best athletes.

The event has changed. I believe the public and media interest has waned because it has lost its place in their minds as a discipline of ultimate stamina and survival. We have American Decathlon Olympic champions now like Bryan Clay, Dan Obrien, and Ashton Eaton, all supreme athletes, but no Time Magazine cover or barely name recognition among the general public. Why? If you were a reporter would you rush to write about the sprinting exploits of Usain Bolt or the Olympic decathlete that is also competing in what has become primarily a test of speed and strength. Decathletes used to be admired most as the Lou Gehrig’s of track and field for their iron horse mind and bodies and ability to survive and endure. With the advent of decathletes becoming primarily sprinters, reporters get lost in the comparison of what the Olympic 100, 200 and 400 meter runners run versus decathletes, and then criticize the decathletes for being a jack of all trades and master at nothing comparable to open event gold medal marks.

I’m glad I got to experience the tail end of the grueling decathlon era. I feel I got to participate in the same event Thorpe, Mathais, Rafer Johnson, Jenner, Toomey and others did. If you are ever on a blog or overhear some athletes say, as I did, guys like Mathias and Rafer Johnson weren’t really that good, I hope this helps explain how the decathlon event has changed and how exceptional they really were.

How is someone like Bob Mathias elevated to the status of American Hero? They do it by becoming god-like. They survive what others can’t fathom attempting, let alone surviving. The long grueling decathlons are what gave Mathias his hero status.

By stumbling on the book, The Bob Mathias Story and The Grueling Decathlon, I found my hero and a skill he inspired me to excel at. Becoming a decathlete paid for my education, I met my wife at the track in college, I have been able to coach and help many other athletes realize their athletic dreams. I had a decathlon career that included making 12 national championship qualifying meets and USA national teams, and got to travel the world.

|

I heard a preacher once say, “Sometimes God winks at us,” explaining further there will be rare times in your life when coincidence alone can’t statistically explain one’s good fortune. It was ten years from June 1973 to June 1983 when I first discovered the book in 8th grade about Bob Mathias and the grueling decathlon. In June 1983, I was invited to train at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs along with five other top ranked U.S. decathletes. By total coincidence, the director of the USOC Training Center was Bob Mathias. As we trained one afternoon, Bob came out to the track and invited all of us decathletes to dinner at his house with his wife, Gwen.

I floated through the door and most of the meal that evening at the Mathias house. What a ten year adventure from that table in the library, to the dinner table of the Mathias home. I really was going to pinch myself during dessert, but stopped for fear of waking up in Eugene, Oregon at 4 am ready to finish a three day decathlon. Worse yet, wake up to learn I interrupted God in the middle of a wink, realize the meal was all a dream, and I never got to thank Bob Mathias when I answered his question, “So Gary, how did you become interested in doing the decathlon?”